Cheshire might represent the platonic ideal of an English landscape: lush green pastures around market towns of sandstone and half-timbered houses, built on a mixed heritage of agricultural and industrial traditions. This has been a cheesemaking country since the time of the Romans, if not before, and that regional delicacy was noted in the mighty medieval survey known as the Domesday Book, circa 1086.

In the mid-20th century, Joseph Heler learned the basics at a local college and bought a second-hand cheese vat and boiler to use at Laurels Farmhouse, the homestead he inherited from his father. His mother had taken to making one cheese a week there, but Joseph wanted to compete with the dozens of businesses then producing at commercial scale. Some 70 years later, says his son Mike, “We’re probably the only Cheshire cheesemaker still around. Father called it ‘stickability’. You need to have ‘stickability’ to survive. And that’s what we as a family have done.”

Mike’s own inheritance is derived from Joseph’s “great work ethic and charisma”, as well as some brave borrowing and judicious investment. Since the early 1990s, the business has grown to 100 staff and expanded to other varieties of cheese, including mild, mature and extra mature Cheddars sold at Spinneys. Having grown up at the farmhouse as the company came to dominate the trade, Mike’s son George is now deeply involved too, and thoroughly initiated in the family recipes.

Together, they can tell you how their cheese is made, but only up to a point. “We’re quite unique in that we still produce in a very traditional way,” says George. Adds Mike: “The beauty of cheesemaking is the science in it. There is a little bit of magic in it too, and a lot of the recipe that we had 30 to 40 years ago is totally in situ today. Perhaps the starter cultures have become more robust, but inherently the way we make cheese has not changed.”

The gist of it comprises “attention to detail, good milk, top-class hygiene and good technique, but we keep that technique under wraps. It’s a secret we don’t reveal.”

Conditions in northwest England are optimal for dairy produce partly because it’s so rainy – the grass grows in healthy, nutrient-rich abundance, and the cows are milked to stringent standards by the farmers of Cheshire, Staffordshire and surrounding counties. Just for example, a farmer named Richard, based just down the road, keeps almost 450 cows on fields so fertile that they can graze out there for eight months of the year.

That herd alone supplies some three-and-a-half million litres a year to the team at Joseph Heler, whose tankers now collect 24/7 from more than 100 other local farms. The milk is then quality-tested onsite, and pasteurised before adding the starter bacteria, rennet and salt. That salt is applied by hand, a job assigned to one specific worker. “When it’s his day off, one other person will do it,” says Mike. “It’s incredibly accurate the way it’s done.”

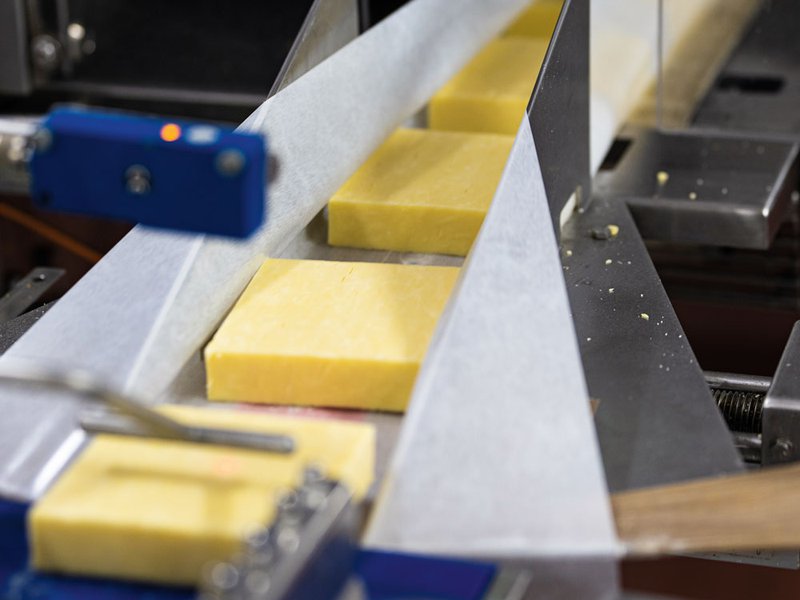

The cheese is then matured for anything from four to six months (for a mild Cheddar), or up to 24 months for a vintage cheese. “Every batch is unique,” says George, “and we select the cheese based on flavour rather than age.” His own taste tends toward the mature. “I like a real depth of flavour. Some sweet notes with savouriness and a nice open, rugged texture.” George’s grandfather was a pioneer in his day, and he sees part of his own role as company custodian to keep making advances. “A lot of our innovation now is around health. Our Eat Lean brand is cheese that’s very high in protein and low in fat, which suits the modern lifestyle. We’re also innovating with sophisticated flavours, using a lot of our blended and wax cheeses.”

At this point, like most successful, long-lived family businesses, Joseph Heler seems to operate on that dual perspective that balances out a respect for its own legacy with a determination to never stale. Mike and George couldn’t be more emotionally invested in their work at Laurels Farmhouse. The former has choice anecdotes from his boyhood when he used to fill a toy pistol with milk to shoot at the cheesemakers, and once found a dog in the middle of a cheese vat.

“Cheesemaking is a lot of hard work,” says Mike, “but you have to retain a sense of humour.” George, meanwhile, is looking toward upgrades to the facilities, new formats and flavours and packaging ideas that will help ensure the sustainability of the operation. “There’s a saying that businesses go from start to finish in three generations. I am not going to be the one to destroy the family empire. We’ve got big ambitions for the future.”