The ancient gods of Mount Olympus gave cheese to mortals as a gift, or so the story goes. Zeus himself had been fed as a baby by the sacred goat Amalthea, and he later flooded the sky with a galaxy of milk to feed his own son Hercules. These mighty figures of Greek mythology, along with legendary monsters like the Cyclops, were written up as avid consumers of feta and kasseri in Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey, circa the eighth century BCE. By that time, many other written records suggest that humans had long since mastered the divine art of cheesemaking.

The Roussas family of Thessaly might be seen as inheritors and custodians of that tradition, making feta (and kasseri) as they do in the manner passed down to them through many centuries of expertise.

The Roussas family age their feta in beechwood barrels

Sheep farmer Leonidas Kitsos

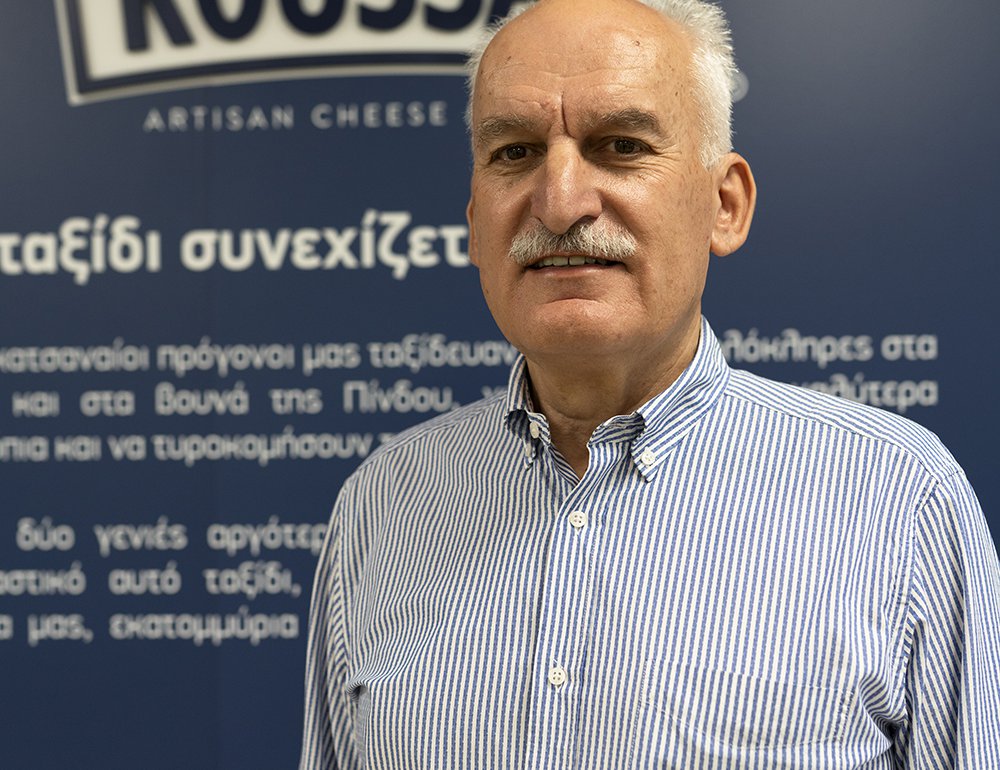

“We try to keep the maximum of ancient techniques in our production,” says Alexandros Botos, who serves as CEO of the company he now runs with three cousins.

“We imitate the old ways, but in a modern dairy with new machinery, and the highest hygiene and quality standards.”

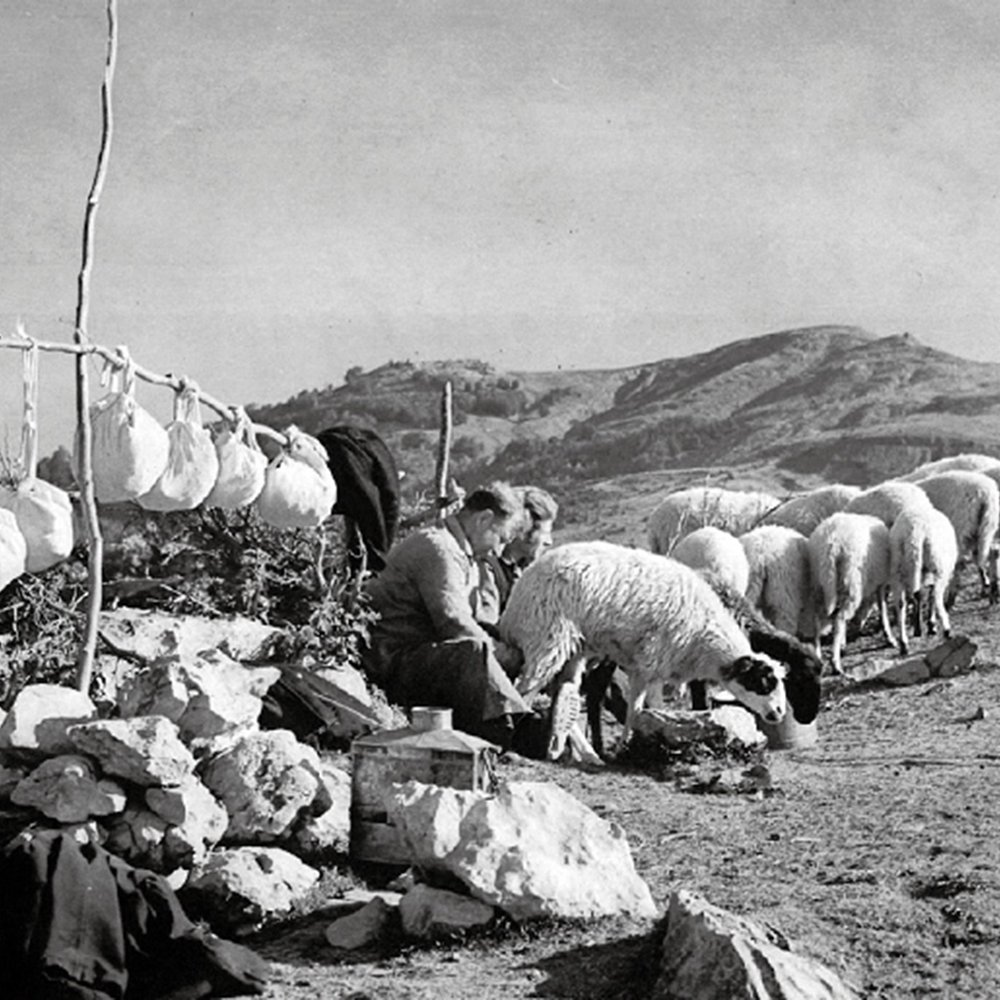

This is not as contradictory as it may sound at first, the old ways in question being those of the Sarakatsani – a tribe of shepherding families, who migrated in seasonal cycles between the mountains and valleys of the region.

When feta cheese is left alone in contact with beechwood, it absorbs the wood’s flavour giving the product its desired sharp taste

John and George Tsimpos handcraft each barrel

“A very proud people forming a small society like a commune and living in a way that did not disturb the environment, they kept their own sheep and a few goats, and never built houses but only tents from straw and wood,” says Alexandros.

His mother and her brothers were all members of that tribe, descended from a long line of nomad farmers who made feta by hand from their herds and cooled it in high caves or lakes. They founded their own dairy in 1952, and having recently celebrated its 70th anniversary, their sons have also lately invested millions of Euros in upgrades that include a new waste treatment facility and a more energy-efficient processing plant powered by photovoltaic cells.

The Sarakatsani were traditionally shepherds

Alexandros Botos, CEO of Roussas Dairy

The business can now produce more than 15,000 tonnes of cheese per year, exporting up to 95% to the US, Europe, Asia and the Middle East, with multiple Roussas products (including regular vacuum-packed, barrel-aged and organic varieties of feta) sold through Spinneys.

“Making feta can be a very simple job when you are producing in small volumes for home consumption, says Alexandros. “Just boil the milk and convert to cheese by adding rennet. When you’re working on large scale it’s more difficult and delicate. You have to take a lot of care with the cheese, and to imitate those old conditions when they made it in caves at low temperatures and high relative humidity.”

Cheese hanging out to dry

Our barrel-aged feta is made to a traditional recipe

That process now begins with filtering, chilling and pasteurising the milk before adding the rennet and cultures. The sheer size of the Roussas operation means stirring vast quantities with huge stainless steel whisks that look something like indoor wind turbines, then cutting the curd into neat cubes with mathematically precise automated blades. About 35% is then set aside in triangular moulds to be strained, rested, then dry-rubbed with Greek sea salt to help it develop the right kinds of bacteria, before it goes into the barrels for ageing.

While the “regular” Roussas feta is fantastic, the closest thing in their range to the ancient artisanal cheese is the kind matured in those beechwood barrels, like Sarakatsani shepherds used to do it.

A Sarakatsani tribe member

Dense forest surrounds the Tsimpos family home

“In the past, the tribe used only natural materials,” says Alexandros. “They had no cold storage, so they would preserve their cheese in barrels made by people who lived in the mountains, who cut the wood from the forest and left it for two years to dry before shaping it by hand. We try to keep up this tradition, and to support the remaining families who work in this way.”

The barrel is no less essential to the process as the cheese itself, and the particular craft of coopering for this purpose is now practised by only a handful of operators in Greece. The Roussas dairy is supplied by a small factory in the northwestern village of Anilio – the name of which means “the place without sun” and refers to its position in the shadows of surrounding peaks and tall black pines, below the ski resort of Metsovo. (The area has its own dairy traditions, reaching across the Pindus mountains to fantastical monastery-topped rock forms known as the Meteora, where the monks made renowned cheeses Metsovone and Metsovela.)

Nikos Tsimpos with his sons George and John

Beechwood drying in the sun

For more than 100 years, the Tsimpos family has felled, rendered, and replanted beech trees in that region of ribbonlike roads through thick woodlands – beech being ideal for maturing cheese because it enhances without overpowering the flavour. Reposing in those Tsimpos barrels for a minimum of three months, the feta is rolled (or “taken for a walk”) at least three times in that period to circulate well before the wood is “cracked” by hand with a hammer.

What comes out, says Alexandros, has special properties derived from the surrounding timbers and the absence of brine. “When we produce in tins, or stainless steel containers, brine represents 10%–20% of the tidal volume. But in a barrel, the cheese is left alone in contact with the wood, absorbing the maximum flavour for a sharper-tasting product.”

The Meteora is a rock formation in Thessaly, Greece, that hosts one of the largest complexes of monasteries

Vassilis Roussas, vice president at Roussas Diary

Which is to say that the beech barrel is the “natural environment for feta”, as far as Alexandros is concerned, and the best means of preserving the floral and herbal aromas of the landscape from which it was sourced. The Roussas work with about 700 farmers of free-roaming herds. Some are based close to the dairy, where a next-generation shepherd named Leonidas Kitsos is bringing that farming culture into the 21st century while still feeding his 1,200-strong flock of sheep on barley sprouts in winter and wild grasses, flowers and herbs in summer. But the brand also draws from many other mountain pastures, all within the bounds of the broad geographic area where Greek feta has been legally classed as a regional product by PDO designation since 2002: Thrace, Macedonia, Sterea Hellas, the Peloponnese and so on.

That spread now allows for a year-round operation based on the continuous coagulation of sheep milk, where formerly that raw material was only available in certain seasons. And while the EU rules around PDO feta allow for the addition of up to 35% goat milk to the mix, the Roussas recipe keeps that quotient down to only 7% or so, for reasons that come back to taste.

“Goat milk can be very sour on the tongue, and using less of it makes a milder cheese that is more consumable around the world,” says Alexandros. He admits to being “very critical” when sampling the feta that bears his family’s name. In many ways he is overseeing a thoroughly modern international business centred on a state-of-the-art production chain, replete with automated pasteurization units, the latest in sustainable packaging tech, and a fleet of trucks with chilled container tanks for transporting ewe milk over and around the high ground once occupied by gods who threw thunderbolts. In other ways – which are literal and practical as much as poetic or romantic – Alexandros is still seeking flavours and fragrances of the past.

“Our parents used to take us into the mountains every summer, for two months or more, to live very close to where our forefathers would come and go for many generations, producing their own food with very simple tools and ingredients. And we would eat the same things they did: the pies made with wheat flour, the cheese made with sheep milk, the veggies grown around the slopes. I have all these memories in my mind when I’m working at the dairy.”